Peace and Values Education

Peace and Values Education (PVE) began at the Kigali Genocide Memorial in 2008 before merging with Rwanda’s national curriculum in 2016. The curriculum utilizes storytelling to teach Rwandan history, genocide studies, and social reconstruction.

Rwandan History

Lesson 1: Historical Context

Created by Leigh-Anne Hendrick

Introduction

Begin with a brief overview of the definition of genocide and its historical occurrences.

Introduce Rwanda using a map (see page 4 of the Rwanda Basics document) and discuss its location in Africa.

Pre-Colonial Rwanda

Divide students into groups.

Assign each group a specific aspect of pre-colonial Rwandan society to research using the provided document and additional resources:

Group 1: Migration Theories and Early Society: Understand the theories of ethnic migration regarding the initial settlement of Rwanda, and discuss how the concept of “nativism” led to tensions between groups. (See page 6 of the Rwanda Basics document for Bantu Migration)

Group 2: Social Structure: Investigate the traditional social structure, including the roles of the Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa. (See page 7 of the Rwanda Basics document for the groups in Rwanda)

Group 3: Ubuhake: Research the Ubuhake system. (See page 8 of the Rwanda Basics document)

Groups will share their findings with the class.

Colonial Influence

Explain the impact of European colonization on Rwanda, focusing on the German and Belgian periods.

Use the provided document to guide the discussion:

German Colonization: Discuss the Berlin Conference, the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty, and German indirect rule. (See pages 9, 10, and 11 of the Rwanda Basics document)

Belgian Colonization: Explain the Mandate System, eugenics, and plantation quotas. (See page 12 of the Rwanda Basics document)

Emphasize how colonial policies exacerbated ethnic divisions and created a racial hierarchy.

Discussion

Discuss how the colonial legacy contributed to social stratification and ethnic tensions in Rwanda.

1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda

The 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda resulted in the murder of one million Tutsi and political moderates by Hutu extremists over one hundred days.

Testimony Activity

Created by the Kigali Genocide Memorial

Adapted by Anne-Sophie Hellman

Instructions: Ask your students to identify a lesson they learned from each of the following stories.

Survivor: Immaculée Ilibagiza

A survivor is a member of a targeted group who lives through a genocide.

Immaculée Ilibagiza is a Tutsi survivor who lived through the 1994 Genocide.

The Rwandan Ministry of Social Affairs and IBUKA estimate that there are between 300,000 to 400,000 survivors of the Genocide Against the Tutsi.

Rescuer: Grace Uwamahoro

A rescuer is a person who saves the life of a member of a targeted group during a genocide. Similarly, an upstander is a person who “stands up” against genocide. They do not participate in genocidal acts; they actively resist them.

Grace Uwamahoro was a 10-year-old Hutu girl who saved the life of Vanessa Uwase, a Tutsi baby, during the 1994 Genocide.

Rescuing poses many risks to the individuals involved due to the constant threat of being caught. For this reason, it is often rare for a person to be a rescuer.

Witness: Edouard Bamporiki

A witness is a person who sees a genocide taking place around them. Another type of witness is a bystander, a person who “stands by” during a genocide. They do not participate in genocidal acts nor do they actively resist them.

Edouard Bamporiki was a 10-year-old Hutu boy who witnessed the 1994 Genocide.

During a genocide, one of the largest demographics are witnesses or bystanders.

Perpetrator: Jean de Dieu Twahirwa

A perpetrator is a person who participates in genocidal acts.

Jean de Dieu Twahirwa is a Hutu man who participated in the 1994 Genocide.

The United Nations estimates that more than 120,000 people committed genocide-related crimes during the Genocide Against the Tutsi.

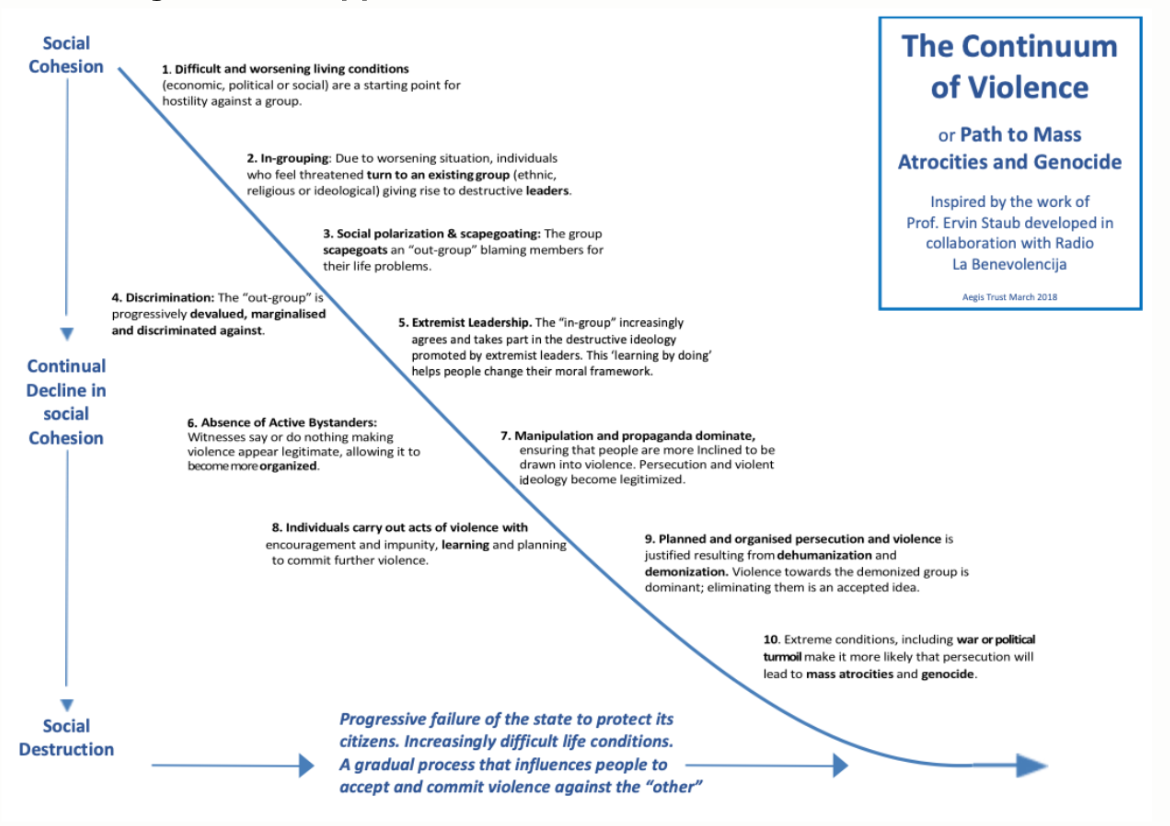

The Continuum of Violence

Created by the Kigali Genocide Memorial

Adapted by Anne-Sophie Hellman

United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide: Article II

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(f) Killing members of the group;

(g) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(h) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about it's physical destruction in whole or in part;

(i) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(j) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

How do ordinary people become perpetrators?

Continuum of Violence Activity

1.Watch “Choosing Cruelty: The Psychology of Perpetrators“

2.Split into groups and match ten terms of the Continuum of Violence (PDF) with their definitions.

3.Discuss parallels between the Continuum of Violence and (historical or current) events in Germany, Rwanda, or the United States.

Content warning: Images of genocide victims and executions

Consequences of Genocide

Created by the Kigali Genocide Memorial

Personal

Physical disabilities: loss of limbs, paralysis, head injuries

Malnutrition; chronic pain

Sensorial disabilities: sight, hearing

Emotional fragility

Chronic grief (traumatic)

Anxiety, depression

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), (witness of traumatic events)

Illness: infected wounds, increase of malaria, HIV/AIDS

Aftermath of rape: children born from rape (approx. 5000)

Stigmatized women and children. Loss of dignity, aversion to men

Loss of close relatives

Personality change and behavioral problems in adults and children

Excessive drinking that was not present before the genocide, and excessive aggression and irritability directed to anybody

Increase of domestic violence, abused children

Group of descendants with PTSD

Resentment (all groups)

Many face psychological stress of anticipating the recurrence of the mass slaughter

The stress and fear of reprisals

Socio-Economic

High number of orphans and widows

Child-headed households

Unfinished education for many young adults

Survivors have to find people who can stand-in for the dead parents

Lack of employable skills

Economic loss for families, loss of possessions, homes, lands

Entire families and extended families completely wiped out

Not having a chance to bury their relatives or perform mourning ceremonies

People fled or were displaced, many families lost connection with their relatives

Shame and guilt among family members of perpetrators

Mutual victimization and climate of mistrust

Survivors are targets of harassment and taunting

National

Destruction of past institutions

Loss of professional competencies

High demand and cost for judicial system, and the Gacaca courts; so many perpetrators

Difficulty in delivering “justice”

High numbers of prisoners in jail

Social and psychological problems, which hinder national unity and reconciliation

Reconciliation requires healing and justice – a huge challenge

Survivors’ desire for justice – and facing fact that they may never see justice

Rights of land conflict (return refugees)

Deforestation from national settlement policy and energy demands of households

Environmental degradation: mass immigration and need for housing means less farming and agricultural land

International

Tension with neighboring countries

Denial: double genocide/negationism

Suspicion about security – conflict from Rwandan diaspora

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

International criticism of efforts to stabilize and bring justice

Failure of international community

Lesson 3: Justice After Genocide

Created by Leigh-Anne Hendrick

Introduction

Before students arrive, create a “Justice Around the Room” silent activity.

Post some of the following prompts on paper or the board and have students answer the prompts that speak the most to them by either writing on paper or putting their answers on post-it notes and sticking them to the board.

“Is justice the same for everyone?”

“Can there be multiple forms of justice?”

“What is the difference between retributive and restorative justice?”

“What does ‘fairness’ mean to you?”

“Can justice and forgiveness coexist?”

“What are some examples of injustice you’ve seen or heard about?”

“Is justice about punishment, healing, or both?”

“What role does community play in justice?”

“What challenges are faced by individuals and society after genocide?”

“How can the consequences of genocide be addressed and overcome?”

“How is it possible to have sustainable peace after genocide?”

After most students are complete, ask a few students to share a thought or response that resonated with them.

Point out common themes or interesting ideas that emerged.

Stress the scale and brutality of the genocide and the need for accountability.

2. Comparing the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and Gacaca

Split students into two groups:

Group 1: ICTR (International justice system)

Group 2: Gacaca (Community-based justice system)

Provide each group with primary sources to analyze:

ICTR: UN Security Council Resolution 955 establishing the tribunal.

Gacaca: Excerpt from “Rwanda: Gacaca Justice” by Penal Reform International.

Each group will analyze:

How does this type of court work? Who are the justices, the lawyers, and how are witnesses identified?

What is the goal and process of the program, or purpose of the system?

How long does it take for justice to be served?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of the program?

Do you think this is the best justice system for Rwanda?

Groups will partner with a student from the opposite group to complete a compare and contrast chart.

3. Writing Prompt

Upon completion of the research and chart, students should answer the following question:

“How do the ICTR and Gacaca courts reflect different understandings of justice, and to what extent did each system contribute to reconciliation and long-term stability in Rwanda?”

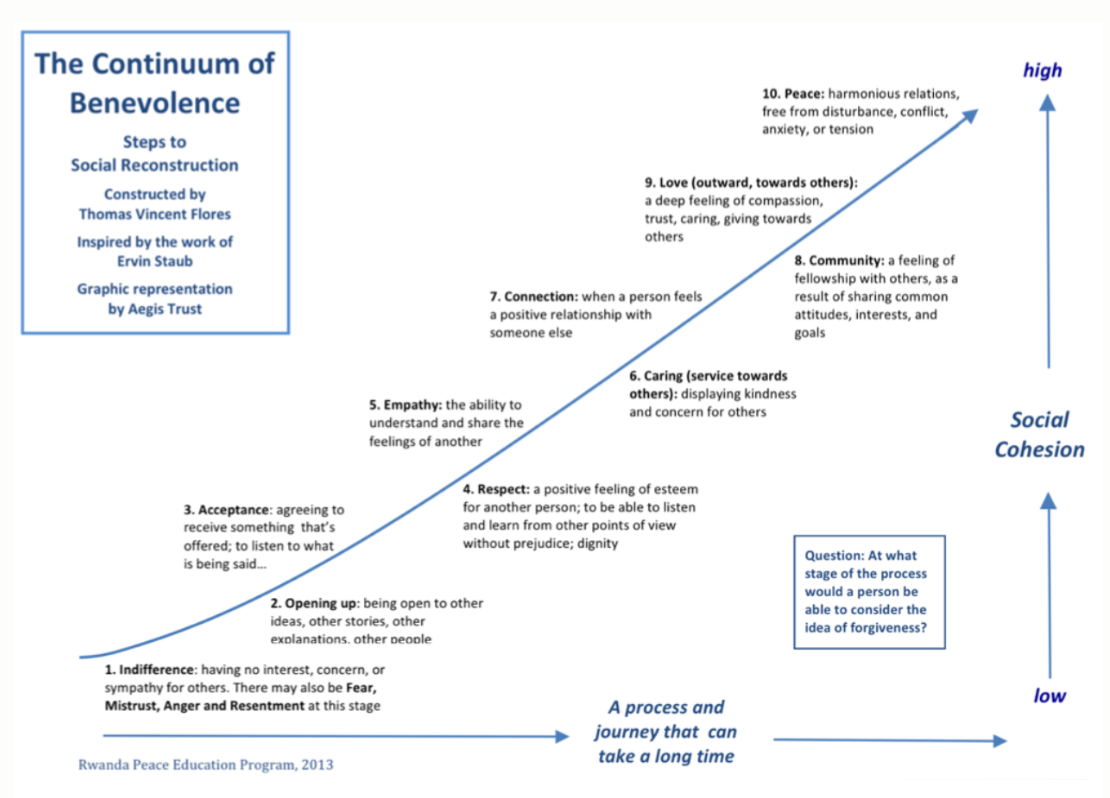

The Continuum of Benevolence

Created by the Kigali Genocide Memorial

Adapted by Anne-Sophie Hellman

Continuum of Benevolence Activity

Hand out slips of paper with one of the ten stages of the Continuum of Benevolence (PDF).

Watch “Albert’s Story: The Power of Forgiveness” and/or “When a former Nazi meets a Holocaust survivor” with your students.

Ask your students to identify where in the videos their stage correlates to.

Content warning: Image of genocide victims.

Enduring Issues Essay

Compiled by Erin Sheehan and Anne-Sophie Hellman

The New York State Global and English Regents exams ask students to write an argumentative essay on enduring issues. This is an opportunity for your students to reflect on the information you have taught them from Sophia’s Legacy, research other genocides and mass atrocities throughout the world, and tie their knowledge together to fulfill the requirements of the Regents exams.

Refer to the Genocide Against the Tutsi Resource List (PDF) for recommended documentaries, books, first-person narratives, oral testimonies, organizations, and curricula.

Refer back to the guidebook for more information and activities.